sample text

So, I use this web-based service to manage book sales, ebook downloads and other jobs on the publishing side of my business (I’m being vague here so as to not name names, though, given the circumstances, I’m not exactly sure why…).

In any case, I pay this company $1000 a year for this service. Not an insubstantial sum of money. And for ponying up a grand, annually, I feel entitled to pick up the phone when I have the occasional technical question, call their toll-free support line and get an answer. Seems pretty fair.

So, I call in the other day with a question, and I’m informed that, as of that day, 10/1, the only way I can get no-charge technical support by phone from now on is if I ante up another 379 bucks a year. Almost 40% of the price of the package I have (their most expensive one).

I give the guy an earful. Which I suspect is about the 50th time that day (being changeover day and all…) he’s been yelled at. He invokes a ridiculous apple-to-oranges analogy of how Microsoft charges for support, until I point out that most people have MS software bundled with their computer when they buy it, so Microsoft isn’t making a ton of money off that sale, making it a bit more logical that they’d charge for support.

He magnanimously allows me to ask my question that day, letting me know that the next time I call I’ll have to pay up. All in all, pretty outrageous, and we could rail on and on about the death of customer service, Companies Behaving Badly, etc. But, the main point of this post is what happened next.

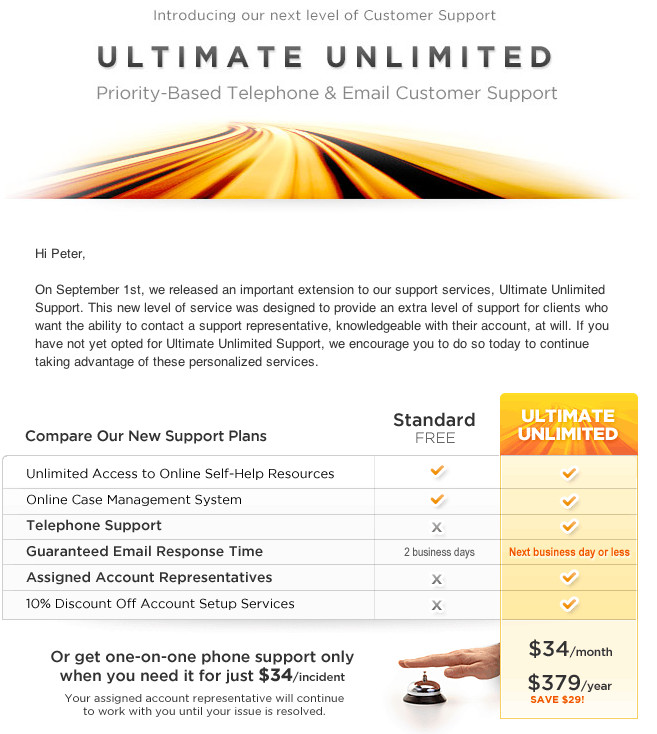

A short time later, I get an email from the company (which they’d apparently sent before 10/1 but I’d missed it) outlining the new service.

Now. Not like I’m right or anything, but my gut tells me that when you’re going to implement a major change to your existing support offering – one that will undoubtedly make a lot of people very unhappy – you don’t compound the inevitable backlash by insulting their intelligence in how you present it…

Here’s how it looked…

Now, tell me. Do you see ANY acknowledgment whatsoever in this email of the hard reality? Specifically, that, “From this day forward, Valued Customer (who gives us $1000 a year, and has been enjoying no-charge phone support as part of that handsome fee), you’ll no longer get it unless you fork over nearly 400 additional clams.â€

Nope. Instead, they blow smoke: “…important extension to our support services…. Ultimate Unlimited Support…extra level of support…blah, blah, blah.†Yeah, they hint around with, “…to continue taking advantage of these personalized services†but nowhere is an honest admission of any kind, something like: “We apologize for this change, but due to rising manpower costs, and overuse of our phone support…etc, etc. etc.†Something, ANYTHING that sounds sincere.

No question, I still wouldn’t have been happy but at least I’d respect them for not insulting my intelligence.

I’ve seen this over and over. Why do companies shun honest communication and opt instead for painfully obvious and laughably ineffective subterfuge? I know, common sense is all too uncommon in Corporate America, but that’s the pat answer. I’m digging for more here.

Don’t they know that we as consumers respond better to honesty? Who was advising them here? All I know, is that if I were hired by a company to write something like this, I’d be sounding the alarm loud and clear that they were making a mistake.

Why DO companies do this?

Can you share any similar examples?

Am I wrong here?

Am I overreacting?

Back in July on this blog, we explored the age-old issue for commercial freelancers: In my commercial copywriting business, should I be a generalist or a specialist? (Read it here).

And when economic times are tough, it takes on even more importance. Which strategy is better in tight times? we ask. Well, grab a seat and join the debate here.

I’ve been a generalist since Day One and I wouldn’t have it any other way. Love the variety, the access to a potentially much wider range of clients and for a bunch of other reasons. Marketing brochures, ad copy, newsletters, direct mail, sales sheets, case studies, speeches, video scripts, sales letters, landing page copy, headlines, tag lines, slogans, naming, book titling. The list goes on and on, and for a soup-to-nuts industry spectrum of companies.

I’ll fully admit that specialists who truly set themselves apart in their niche will likely make more money than me, and that’s just fine. I’d be a very unhappy camper if I had to do the same kind of project or write for the same kind of industry all the time.

Sort of like the guy who’s told by his doctor that if he doesn’t quit smoking, drinking and eating rich foods (all the stuff he enjoys), he’s only got 5 years to live, and but he’s got 10 if he cuts out all those bad things. And he decides, heck, I don’t WANT to live five years longer if I can’t enjoy those things.

Anyway, we’re not done with the Generalist/Specialist debate – literally and figuratively. I invite you to join yours truly, Peter Bowerman, Mr. Generalist – who’s made a most comfortable living writing for clients across the spectrum for going on 16 years – and Mr. Specialist, Michael Stelzner – who’s done pretty darn well focusing exclusively on white papers for many years – in a lively debate.

Thursday, September 17 at 3:00 EST for an hour. Be there.

There’s no charge for the event, but you need to register here to join us. Can’t join us? Register anyway and we’ll send you the recording!

We’ll debate the pros and cons of both sides (AND take your questions). And when we’re done, you’ll have the inside scoop on which path makes the most sense for you and your circumstances…

Don’t miss it!

Screw-ups. We all have ‘em. With friends, family, and yes, with our commercial writing clients. But, how you deal with it can be far more important than the screw-up itself. This subject may be a bit off the mainstream of commercial writing, but thought it was worth knocking around, and certainly has relevance for our copywriting businesses.

Last week, one of my copywriting colleagues stepped in it after sending out a note about a coaching client and a niche that client had developed, and sent a link to a YouTube video featuring that client prominently on one side of contentious political issue.

Later that day, once realization dawned (no doubt spurred by some angry notes), out went the mea culpa, saying, in essence, “I didn’t mean to promote a political point of view, and have been so busy lately doing this and that that I neglected to ‘consider the content’ of what I sent out.â€

In the wake of that, I got an email from a reader, saying, “Upon reading her apology I unsubscribed from her list†(having just subscribed a few days earlier). She went on to point out that, “not ‘considering the content’ showed little respect for one’s recipients, which, in turn, ends up losing, not gaining interest and goodwill.â€

Finally, and most importantly, she took offense at my colleague’s apology, which was less of an apology and more of an excuse, citing “busy-ness†with this and that unrelated task and, as a result of that preoccupation, not thinking it through.

As my friend explained, “When we make a mistake, don’t we have an obligation to own it? With a different sort of apology I might not have unsubscribed. Something like: ‘Today I distributed a video featuring one of my clients. I regret sending it. The video did not demonstrate the point I was hoping to make, and in fact contained a political message many of you may have found inappropriate and offensive. I apologize. Please be assured that nothing like this will happen again.’ But instead she made excuses.â€

Which made me think about the nature of apologies. In follow-on emails, we both sympathized with my colleague’s compounded error. You make a mistake, and in trying to apologize, it’s only human to want to make yourself look good (or less bad). You’re faced with a) frankly admitting no-excuse cluelessness, or, b) claiming the excuse of distracted carelessness (who can’t relate to being too busy?). In this case, my colleague chose the latter. And perhaps it worked on some, but certainly not on my friend.

I bring up this episode NOT to gang up on my colleague anymore (who no doubt took themselves to the woodshed several times), but to use it as a discussion starter about the nature of apologies. I’ve certainly apologized in the past like my colleague did, so I can’t throw stones. But now (perhaps based on the results of that approach), I put myself in the second camp. If I screw up, I’ll throw myself to the wolves – no excuses.

One of the things I’ve learned in my years on earth is that, overwhelmingly, people are just looking for reasons to forgive you. Do a soft-shoe, deflect and dissemble and they’ll pound you doubly hard. Perhaps because they’re punishing you for that same slippery quality they hate in themselves.

But, come to them with a clear-eyed admission of guilt, hat in hand, no excuses, and they’ll fall all over themselves to offer you absolution. Perhaps, because, by the same token, they’re rewarding you for showing the same flawed humanness they share with you, a humanness they know takes courage to reveal. And they’ll not only forgive you, you’ll grow in stature in their eyes. Sometimes irrationally…

Caught a news item last week about Lt. Calley of My Lai (Vietnam) massacre infamy, who, 41 years after the fact, finally apologized for his role in the cold-blooded murder of 500 unarmed Vietnamese civilians – mostly women and children. He did it at a Kiwanis Club meeting in Columbus, Georgia, where afterwards – you ain’t going to believe this – the assembled attendees gave him a standing ovation.

If that isn’t proof that people love to be magnanimous (and will actually think better of you no matter what you did), whether or not they should be, I’m not sure what is.

Can you share a time you apologized to a client in a no-excuses manner and how did it turn out?

Can you share a time you apologized to a client by making excuses and how did that turn out?

Any other thoughts on apologies?